Rizzolatti, G., & Craighero, L. (2004). The Mirror-Neuron System. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 27.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8491604_The_Mirror-Neuron_System

McLeod, S. (n.d.). Albert Bandura’s Social Learning Theory. SimplyPsychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/bandura.html

Okon-Singer, H., Hendler, T., Pessoa, L., & Shackman, A. J. (2015). The Neurobiology of Emotion-Cognition Interactions: Fundamental Questions and Strategies for Future Research. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, 58. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4344113/

Edmondson, A. C. (2019). The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth. Wiley.

Delizonna, L. (2017). High-Performing Teams Need Psychological Safety. Here’s How to Create It. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2017/08/high-performing-teams-need-psychological-safetyheres-

how-to-create-it

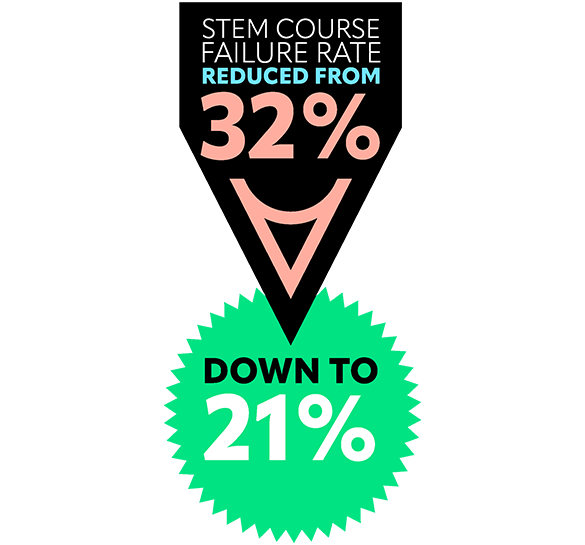

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410–8415. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4060654/

Caspers, S., Zilles, K., Laird, A. R., & Eickhoff, S. B. (2010). ALE meta-analysis of action observation and imitation in the human brain. Current Biology, 20(8),

738–743. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0960982210002332